The image of Christ during the last hours before his crucifixion, commonly known as “Christ in the Dungeon”, is one of the most well-known subjects in religious sculpture. Usually, Christ is depicted sitting, with his head wearily lowered. A crown of thorns is placed on his head and drops of blood can be seen running down his face. Traces of flogging can be seen on his back, arms, and legs. The origin of this iconography dates to the year 1511, when Albrecht Dürer’s graphic series “The Passion”, featuring the image of suffering Christ on its front sheet, was published.

The 18th century witnessed a resurgence of interest in this tragic subject, and it spread to Eastern Europe, particularly Russia, where it became a popular motif of Pensive Christ, or Midnight Savior, and could be found in every provincial church. Russian artists did not simply copy Western models but rather freely interpreted both the appearance of Jesus and even the iconography itself.

In the 20th century, this image, along with other biblical subjects, found its way into the works of many European artists. They were not intended to be displayed in churches. The search for the origin in Christian iconography, its thoughtful modern interpretation, and the emphasis on emotional impact brings the religious story closer to the contemporary viewer.

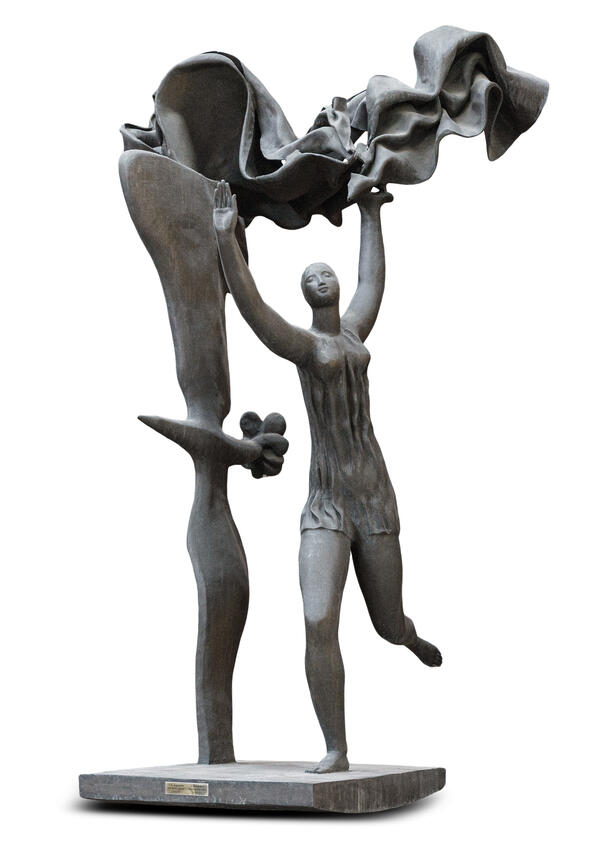

With this in mind, Alexander Burganov created his “Christ in the Prison”. Christ is depicted as sad and deep in thought, as if in his own world. He seems detached from the painful reality, having been subjected to insults and physical abuse. His right hand is raised to his face, not to cover his head from the blows, but merely support its weight, which endows the image with a sense of mournful contemplation. Burganov pays special attention to the interpretation of the human body in his work. In his “Christ in the Prison”, the sculptor stripped the figure of Jesus of all material and physical elements. The body’s shape is distinctly geometric. The sculptor decided against a realistic portrayal associated with the suffering of flesh, in order to convey the sublime and mournful nature of the spirit rather than the physical pain.