The name of Grigory Vasilyevich Safontsev is mentioned in the appendix “Photographers and Photographic Studios of Pre-Revolutionary Russia” on the website “Big Russian Album”. He appears there as a prominent artist who owned his own photo studio and branded mats (passe-partout).

The studio was located on a glazed veranda as it was the brightest room. Until the end of the 19th century, photoshoots took place only in natural light, hence, the studio was open from 10 am to 3 pm and only in clear weather. In order to achieve not just sufficient, but also even, correct lighting, the ceiling was covered with sliding curtains: with their help, it was possible to adjust the light falling from above. Both windows and the northern wall, which was not in direct sunlight, let in even, diffused light. The southern wall, on the contrary, remained closed, as direct sunlight could cause glare on the faces and clothes of customers.

In the 1880s, with the advent of electric lighting, strict requirements for time and weather conditions were reduced, and studios could work in the evenings. When the use of flash became fashionable, the client could arrange a session with the photographer at any convenient time.

The design of photographs was regulated by the “Press Law” of 1865. In particular, it stipulated the need to hand over to customers only those photographs that were attached onto branded mats. Initially, these cardboard frames were of arbitrary sizes according to the customer’s wishes. In 1890, passe-partout of standard formats came into use: there were business card, minion, cabinet, stereoscopic, boudoir, imperial and panel formats. The “panel” format was usually ordered for printing family photos. The most popular were business cards and cabinet portraits. The former were not only given as mementos, but also often used as identity cards: for such use of a photo, only a corresponding mark certified by an official was required. The latter were stored in albums or frames.

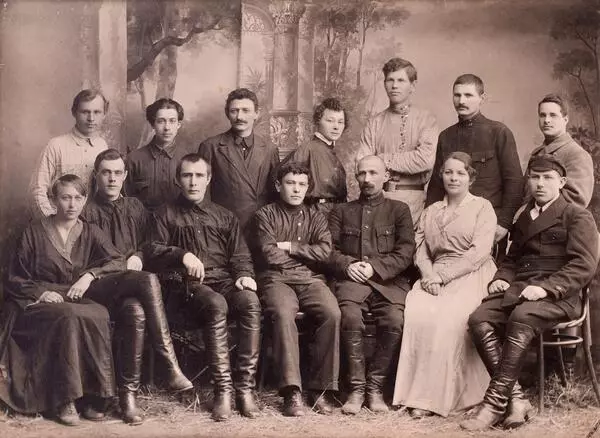

A session with a photographer was not cheap. Six copies of the cabinet portrait cost four rubles, the same number of business cards — one and a half. Based on purely practical considerations, customers preferred to take group pictures and every one chipped in.

The museum staff managed to replenish the collection of old photographs by contacting the residents of Borisovka through social networks and district newspapers with a request to share their archives. Some donated the original pictures as a gift, others provided them for a time being, for converting them into digital formats.

The studio was located on a glazed veranda as it was the brightest room. Until the end of the 19th century, photoshoots took place only in natural light, hence, the studio was open from 10 am to 3 pm and only in clear weather. In order to achieve not just sufficient, but also even, correct lighting, the ceiling was covered with sliding curtains: with their help, it was possible to adjust the light falling from above. Both windows and the northern wall, which was not in direct sunlight, let in even, diffused light. The southern wall, on the contrary, remained closed, as direct sunlight could cause glare on the faces and clothes of customers.

In the 1880s, with the advent of electric lighting, strict requirements for time and weather conditions were reduced, and studios could work in the evenings. When the use of flash became fashionable, the client could arrange a session with the photographer at any convenient time.

The design of photographs was regulated by the “Press Law” of 1865. In particular, it stipulated the need to hand over to customers only those photographs that were attached onto branded mats. Initially, these cardboard frames were of arbitrary sizes according to the customer’s wishes. In 1890, passe-partout of standard formats came into use: there were business card, minion, cabinet, stereoscopic, boudoir, imperial and panel formats. The “panel” format was usually ordered for printing family photos. The most popular were business cards and cabinet portraits. The former were not only given as mementos, but also often used as identity cards: for such use of a photo, only a corresponding mark certified by an official was required. The latter were stored in albums or frames.

A session with a photographer was not cheap. Six copies of the cabinet portrait cost four rubles, the same number of business cards — one and a half. Based on purely practical considerations, customers preferred to take group pictures and every one chipped in.

The museum staff managed to replenish the collection of old photographs by contacting the residents of Borisovka through social networks and district newspapers with a request to share their archives. Some donated the original pictures as a gift, others provided them for a time being, for converting them into digital formats.