Early studio photography starkly differed from the modern one. Bulky vintage cameras were installed on the floor. Poor-quality photo lenses and low sensitivity of the photographic emulsion required a long exposure. In order to achieve good lighting, photographers preferred to work in glass pavilions, which were well-lit, including through the ceiling. The use of a flash was necessary, but it also presented a fire hazard: flash powder, made of magnesium, was put onto a metal tray with a long handle and lit. Even with very careful movements of the photographer, the room was filled with smoke and the smell of burning.

Knowing about all these difficulties, people tried to take a comfortable pose and, as a rule, did not smile. However, the lack of smiles can be explained not only by the unwillingness to strain the face muscles for a long time, but also by the special etiquette of making a ceremonial portrait.

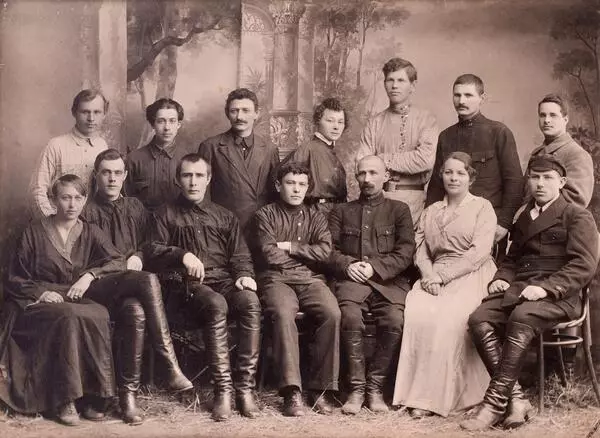

At the turn of the 20th century, photo studios and the process became more enjoyable. There was a need for soft and diffused lighting. The photographer’s tools included backdrops with images of landscapes and architectural structures, props, and interior items: a table, a chair with a high back and armrests, railings, curtains, and vases. The set was quite limited, but it still enlivened the ambiance.

The photograph presented in the exhibition shows people captured against the backdrop of a “bourgeois” landscape with classical columns, which did not really fit the new socialist ideology.

The First of May was called Labor Day, or the Day of International Workers Solidarity, and had a pronounced socio-political character. Grigory Vasilyevich Safontsev, a photographer who chronicled the life in Borisovka before the Russian Revolution, continued his peculiar chronicle after 1917. Back then, by order of the authorities, he captured historically significant moments: rallies, agricultural exhibitions, ceremonies of handing over acts permitting collective farmers to use their lands indefinitely, columns of wagons with crops, and official holidays. While working at an industrial plant, he made photocopies of party documents. Safontsev continued to create artistic portraits as well: they were, as a rule, group shots of model workers. Despite all his contributions, at the end of his life he was denied a pension as he used to keep his own photo studio under the tsarist regime.

Knowing about all these difficulties, people tried to take a comfortable pose and, as a rule, did not smile. However, the lack of smiles can be explained not only by the unwillingness to strain the face muscles for a long time, but also by the special etiquette of making a ceremonial portrait.

At the turn of the 20th century, photo studios and the process became more enjoyable. There was a need for soft and diffused lighting. The photographer’s tools included backdrops with images of landscapes and architectural structures, props, and interior items: a table, a chair with a high back and armrests, railings, curtains, and vases. The set was quite limited, but it still enlivened the ambiance.

The photograph presented in the exhibition shows people captured against the backdrop of a “bourgeois” landscape with classical columns, which did not really fit the new socialist ideology.

The First of May was called Labor Day, or the Day of International Workers Solidarity, and had a pronounced socio-political character. Grigory Vasilyevich Safontsev, a photographer who chronicled the life in Borisovka before the Russian Revolution, continued his peculiar chronicle after 1917. Back then, by order of the authorities, he captured historically significant moments: rallies, agricultural exhibitions, ceremonies of handing over acts permitting collective farmers to use their lands indefinitely, columns of wagons with crops, and official holidays. While working at an industrial plant, he made photocopies of party documents. Safontsev continued to create artistic portraits as well: they were, as a rule, group shots of model workers. Despite all his contributions, at the end of his life he was denied a pension as he used to keep his own photo studio under the tsarist regime.