Most of the photographs taken by Grigory Vasilyevich Safontsev entered the collection of the Borisovka Museum of Local History thanks to donors.

It is sometimes possible to establish the names of the captured people and even their occupation by examining the signatures on the mats or relying on the owners’ testimony. Otherwise, for example, the degree of kinship can only be assumed judging by external similarities. In order to save money, customers preferred group shots, which could include both relatives and friends or colleagues.

The director of the museum, Diana Nikolaevna Novitskaya, noted in an interview the liveliness and expressiveness of the faces in these photographs, “After all, being photographed was a very important event for people of that time. They put on their best clothes, and if there were no such outfits in the wardrobe, they borrowed clothes and shoes from friends.”

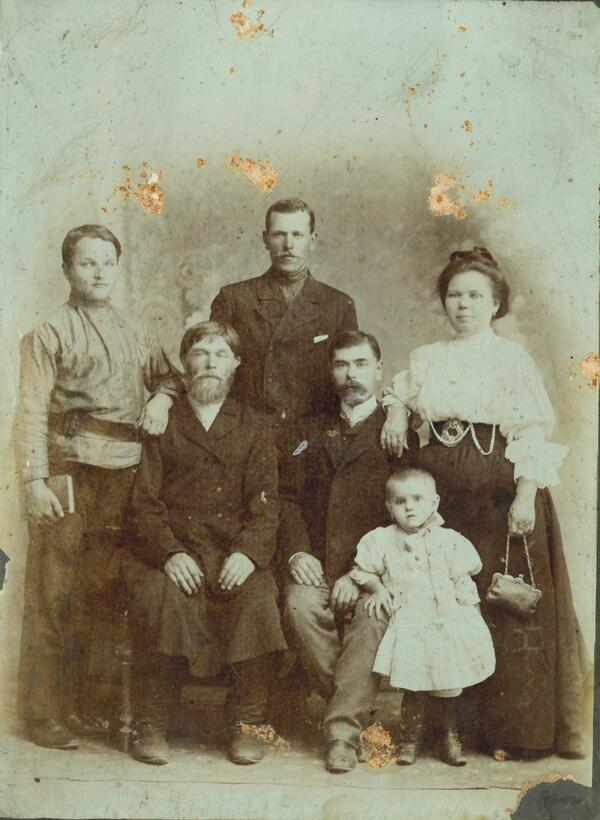

It was possible to identify the names of three people who posed for this photo: a woman and two sitting men.

Antonina Ivanovna Volkova (nee Kabychenko) is dressed in clothes fashionable in the early 20th century: a floor-length high-waisted skirt, a pastel blouse with tucks, and she has a small purse in her hand. The woman wears a neat hairstyle — a kind of streamlined pompadour. In the late 19th century, under the influence of widespread fascination with Japanese culture, “geisha hairstyles” became popular: complex horsehair attachments were used to create them. This fashion lasted until the 1920s, but gradually only echoes of it remained. In general, women’s hairstyles in the early 20th century were characterized by simplicity and naturalness.

Ivan Kabychenko, Antonina Ivanovna’s father, was an icon painter. By the time the picture was taken, the art of icon painting became a craft, about 500 people were engaged in it in Borisovka. There were no more than 50 colorists among them who could paint the entire image; other masters called lichkuns only painted the faces and hands, as icons were covered with revetments. There were only a few true master colorists. The era of artisan icon painters ended at the turn of the century, when they learned to print icons using lithography.

Mikhail Khomchenko worked as a miller at the first windmill in Borisovka. The sails of this mill rotated around a vertical axis in a horizontal plane. First mills had from 6 to 12 sails, they were covered with a reed mat or cloth. Such structures were used for grinding grain or collecting water.

It is sometimes possible to establish the names of the captured people and even their occupation by examining the signatures on the mats or relying on the owners’ testimony. Otherwise, for example, the degree of kinship can only be assumed judging by external similarities. In order to save money, customers preferred group shots, which could include both relatives and friends or colleagues.

The director of the museum, Diana Nikolaevna Novitskaya, noted in an interview the liveliness and expressiveness of the faces in these photographs, “After all, being photographed was a very important event for people of that time. They put on their best clothes, and if there were no such outfits in the wardrobe, they borrowed clothes and shoes from friends.”

It was possible to identify the names of three people who posed for this photo: a woman and two sitting men.

Antonina Ivanovna Volkova (nee Kabychenko) is dressed in clothes fashionable in the early 20th century: a floor-length high-waisted skirt, a pastel blouse with tucks, and she has a small purse in her hand. The woman wears a neat hairstyle — a kind of streamlined pompadour. In the late 19th century, under the influence of widespread fascination with Japanese culture, “geisha hairstyles” became popular: complex horsehair attachments were used to create them. This fashion lasted until the 1920s, but gradually only echoes of it remained. In general, women’s hairstyles in the early 20th century were characterized by simplicity and naturalness.

Ivan Kabychenko, Antonina Ivanovna’s father, was an icon painter. By the time the picture was taken, the art of icon painting became a craft, about 500 people were engaged in it in Borisovka. There were no more than 50 colorists among them who could paint the entire image; other masters called lichkuns only painted the faces and hands, as icons were covered with revetments. There were only a few true master colorists. The era of artisan icon painters ended at the turn of the century, when they learned to print icons using lithography.

Mikhail Khomchenko worked as a miller at the first windmill in Borisovka. The sails of this mill rotated around a vertical axis in a horizontal plane. First mills had from 6 to 12 sails, they were covered with a reed mat or cloth. Such structures were used for grinding grain or collecting water.