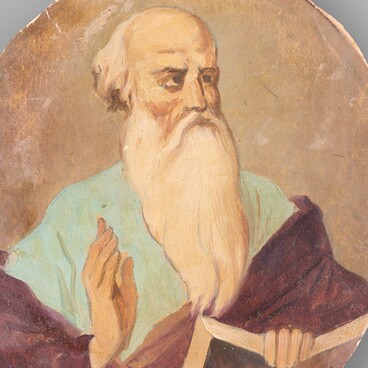

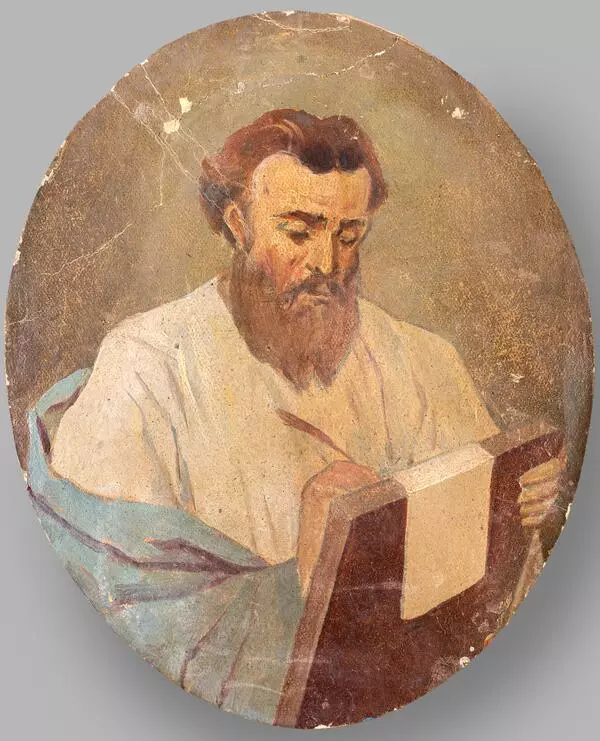

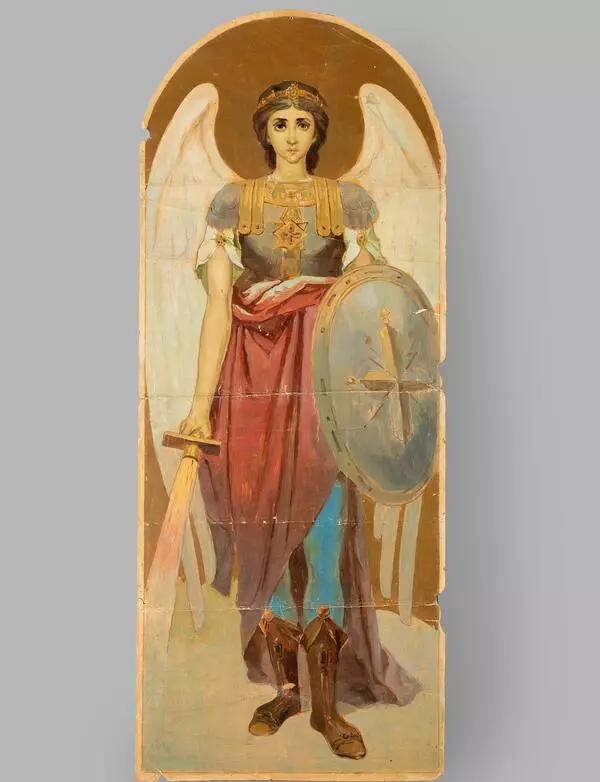

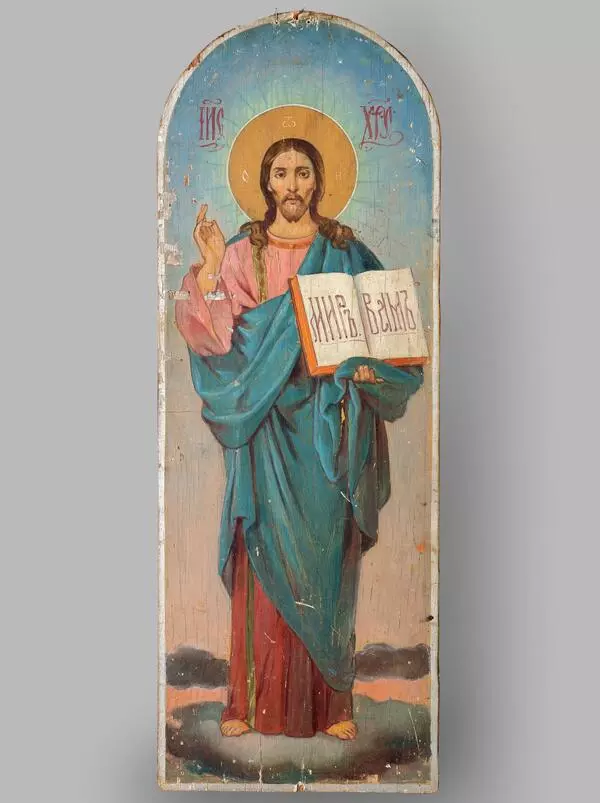

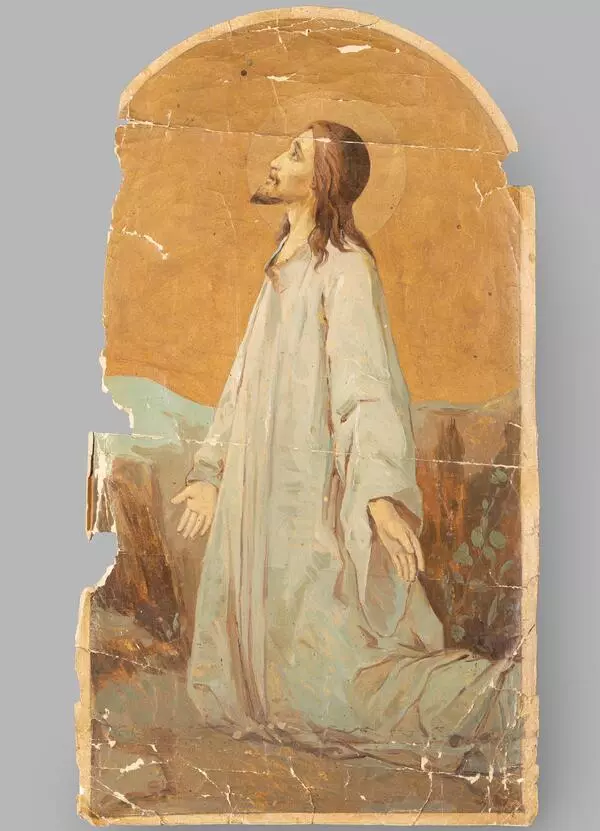

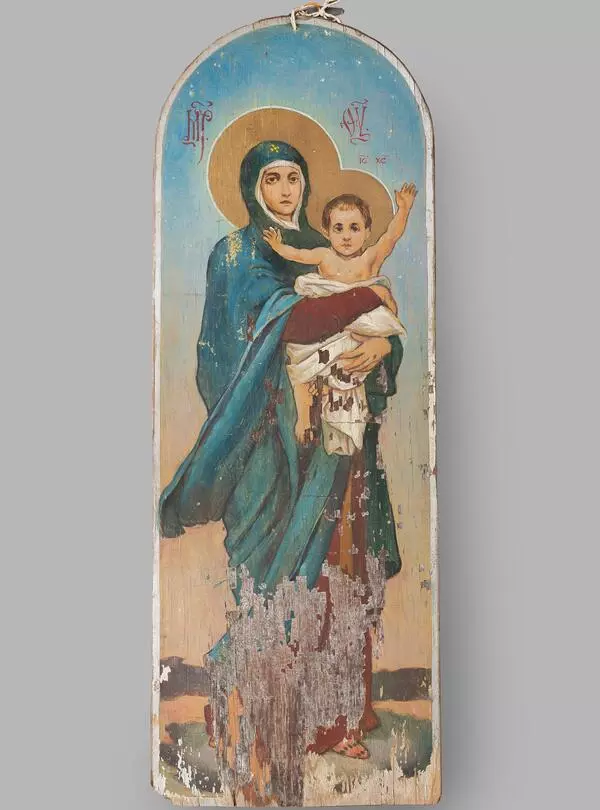

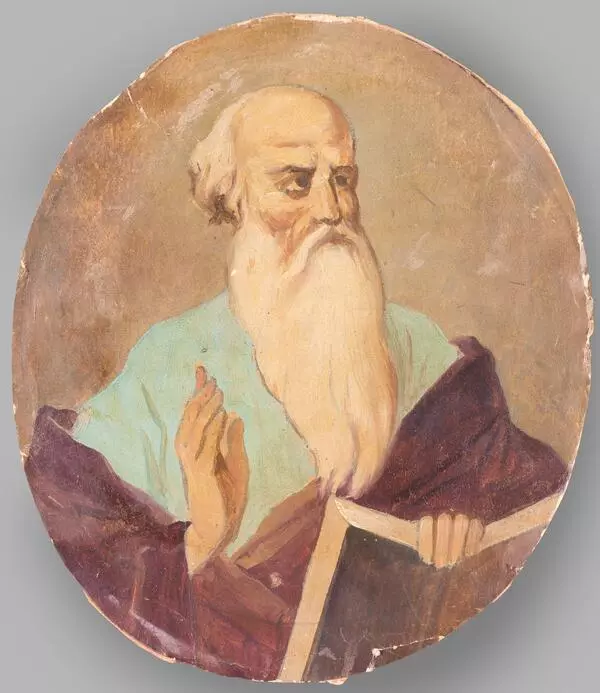

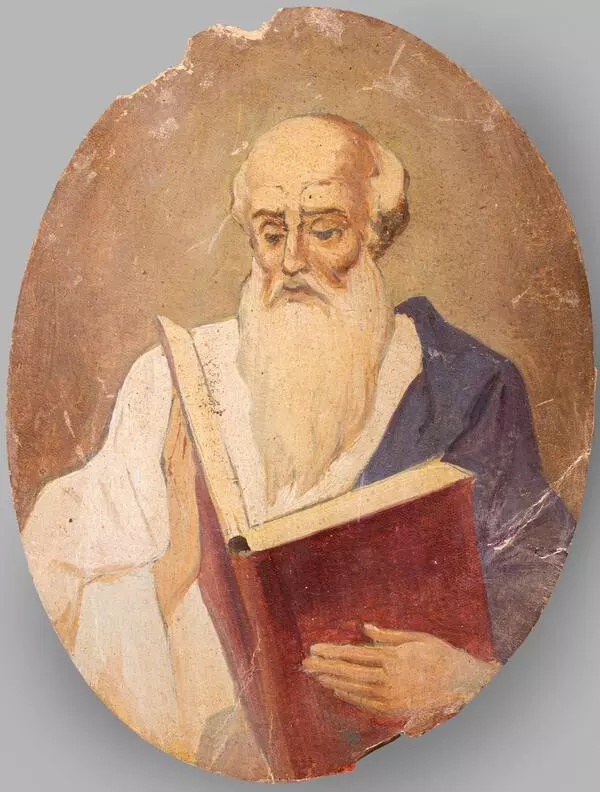

Mikhail Ivanovich Khvostenko, a hereditary Borisovka artist, graduated from a local icon painting workshop in 1907. The graduation certificate stated that Khvostenko was awarded the title of master icon painter. At first Khvostenko painted churches, but after the Russian Revolution he began to work on orders of a different kind: he created posters and paintings on paper and outline maps. Among them there were views of the artist’s small homeland.

“My Father’s House” is not an abstract title. The painting depicts the house of Mikhail Ivanovich’s parents. Wattle-and-daub houses called mazankas were the most common type of dwellings among the southern Slavic peoples: western and southern Russians, Belarusians, Poles and especially Ukrainians. Solid walls — at least half a meter thick — were made of clay or mudbrick; less often wall frames made of poles or wattle were used. Outside and inside they were coated with clay; the house was covered with a hip roof made of reeds or straw soaked in clay.

Until the mid-20th century, a wooden floor in wattle-and-daub houses was a rarity: as a rule, its role was performed by tightly packed earth, which was covered with a mixture of clay and mudbrick. The walls and floor were plastered, initially, using a solution of white clay (it was taken in the vicinity of the Tikhvin Monastery) and fresh horse droppings, which were considered beneficial for one’s health. Over time, when people stopped using horses as much, the traditional solution was replaced with lime mortar.

The interior of the mazanka was divided into two parts: the front, facing the street, and the back, facing the courtyard. They were separated by the stove (a “gruba” — a simplified version of the Russian stove) and a partition made of wattle. The inner porch was on the back side. The front part was considered a ceremonial one: guests were greeted, icons were placed, and the family rested there. In the back part, they heated the stove, cooked and stored food, kept household equipment, and in colder temperatures, allowed young poultry and livestock to stay there.

At least twice a year, before Christmas and on Maundy Thursday, the house was whitewashed, and in autumn, when there was free time, the family painted the red corner, the stove, the walls and ceiling.

Writers and travelers who visited mazankas always noted their cleanliness and neatness, and especially the greenery in which the “white tents” were buried.

“My Father’s House” is not an abstract title. The painting depicts the house of Mikhail Ivanovich’s parents. Wattle-and-daub houses called mazankas were the most common type of dwellings among the southern Slavic peoples: western and southern Russians, Belarusians, Poles and especially Ukrainians. Solid walls — at least half a meter thick — were made of clay or mudbrick; less often wall frames made of poles or wattle were used. Outside and inside they were coated with clay; the house was covered with a hip roof made of reeds or straw soaked in clay.

Until the mid-20th century, a wooden floor in wattle-and-daub houses was a rarity: as a rule, its role was performed by tightly packed earth, which was covered with a mixture of clay and mudbrick. The walls and floor were plastered, initially, using a solution of white clay (it was taken in the vicinity of the Tikhvin Monastery) and fresh horse droppings, which were considered beneficial for one’s health. Over time, when people stopped using horses as much, the traditional solution was replaced with lime mortar.

The interior of the mazanka was divided into two parts: the front, facing the street, and the back, facing the courtyard. They were separated by the stove (a “gruba” — a simplified version of the Russian stove) and a partition made of wattle. The inner porch was on the back side. The front part was considered a ceremonial one: guests were greeted, icons were placed, and the family rested there. In the back part, they heated the stove, cooked and stored food, kept household equipment, and in colder temperatures, allowed young poultry and livestock to stay there.

At least twice a year, before Christmas and on Maundy Thursday, the house was whitewashed, and in autumn, when there was free time, the family painted the red corner, the stove, the walls and ceiling.

Writers and travelers who visited mazankas always noted their cleanliness and neatness, and especially the greenery in which the “white tents” were buried.