In Orthodox Christianity, there are three choirs, or orders, of angels, each of which has three ranks. They differ in their closeness to God and the type of service they perform.

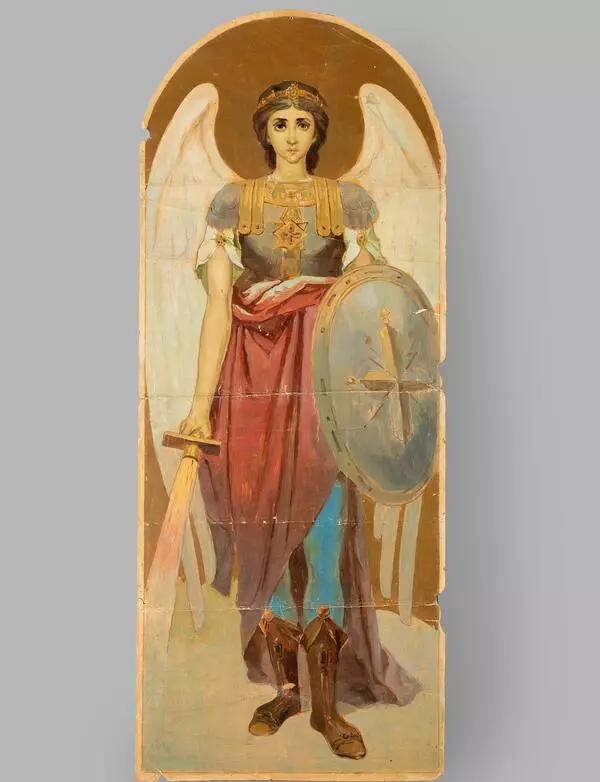

Archangels belong to the third order and are revered as commanders of other angels. They are mentors and heralds of the Lord’s will among people; through them God sends His Revelations to the righteous.

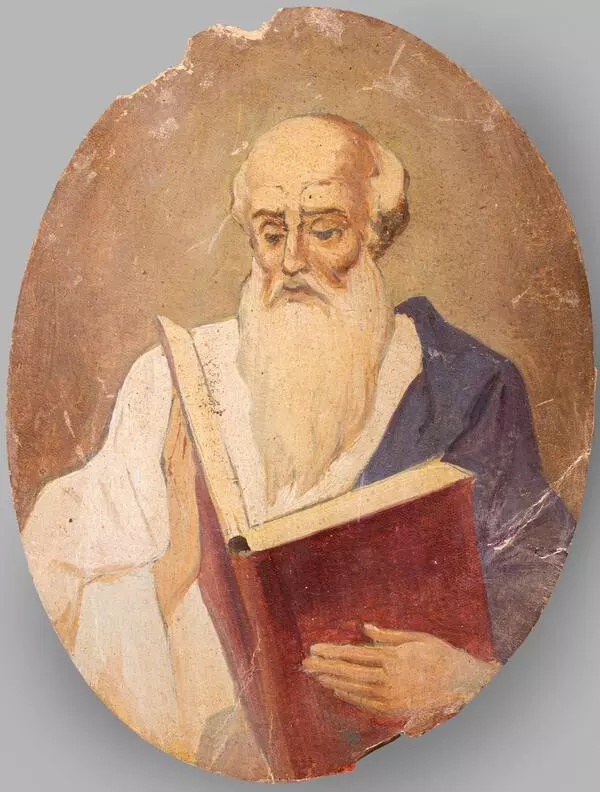

The Archangel Gabriel is usually called the second in the hierarchy after the Archangel Michael, the Archistrategos. Not all the Church Fathers agreed to recognize this particular place of Gabriel in the hierarchy. St. Andrew of Crete wrote that only a spirit who is constantly in the presence of God, closest to the throne of the Lord, could be awarded the right to carry the message about Christ’s upcoming birth. Thus, Gabriel should not be considered an archangel, but a seraph (the supreme angel). Saint Gregory the Great believed that just like Eve was tempted by the Prince of Darkness himself, only a seraph could have come to Mary who had a “flaming Seraphim’s love” for the Lord. However, the official church tradition calls Gabriel an Archangel and a “servant of miracles.” The archangel says the following in the text of the Gospel: “I am Gabriel, that stand in the presence of God” (Luke 1:19).

Most often, a mirror made of green jasper is depicted in the hands of the Archangel Gabriel as a sign of the messenger who “announces salvation of humankind” and a lantern with a burning candle. St. Dimitry of Rostov explains this attribute by the fact that the providence of God is hidden and only those are granted the ability to comprehend it who “always look into the mirror of the word of God and their own conscience.”

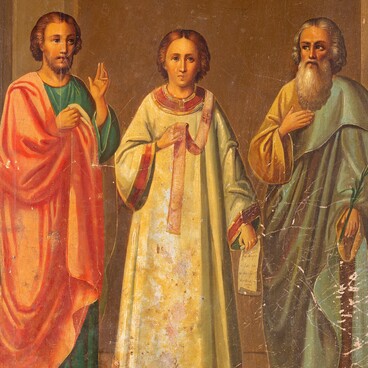

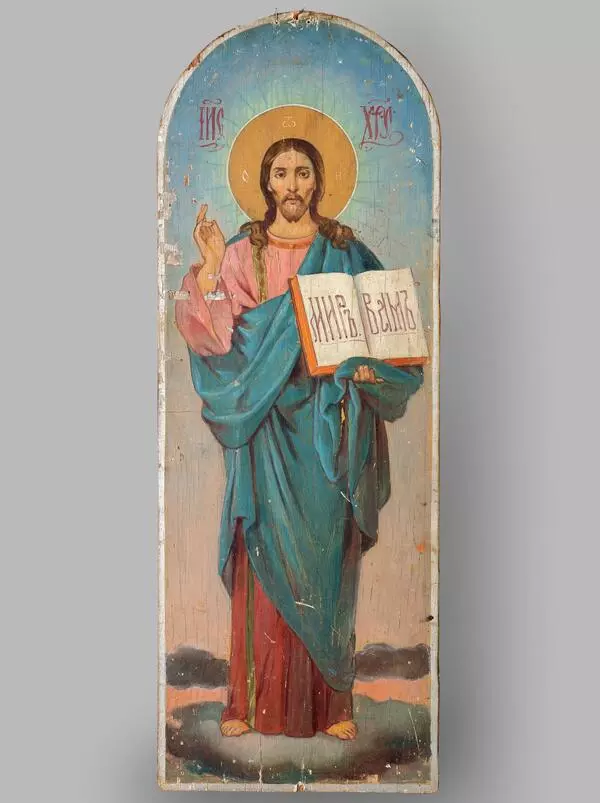

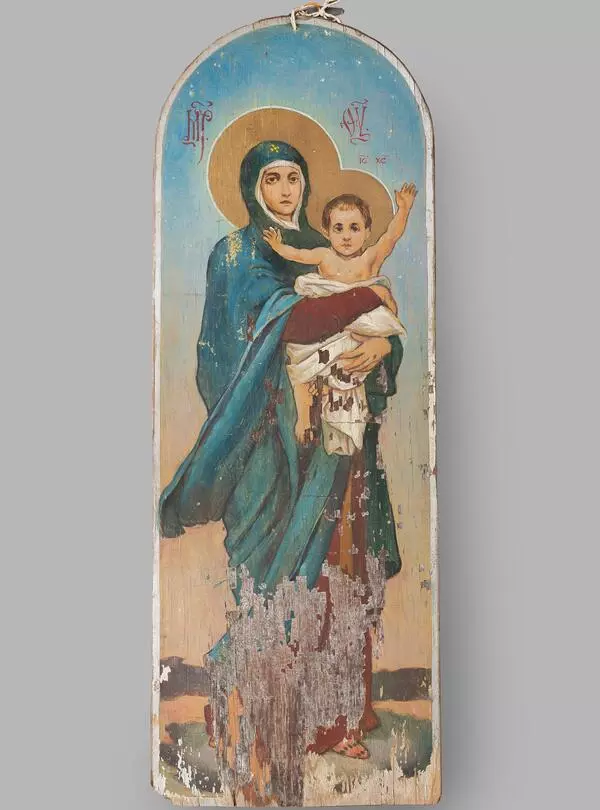

Although all heavenly forces are disembodied by nature, they appear to people in the form that is accessible and familiar to human perception. That is why, at the dawn of Christianity, when early Christians drew images on the walls of the catacombs, the Archangel Gabriel appeared as a beautiful man or a young boy without a halo and wings, dressed in a tunic and pallium (a band of lamb’s wool, a symbol of the archbishop’s power).

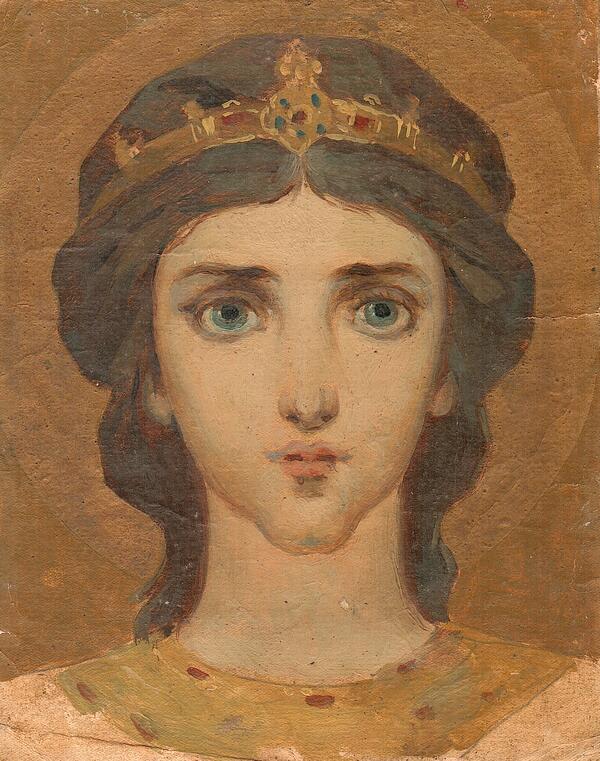

Later, a canon of depicting angels was formed: it prescribed to paint them with youthful faces, a halo, usually white wings, a tiara or a headband, symbolizing that the attention of the heavenly messengers was focused on the will of God. Sometimes the image was complemented by lavish robes.

Archangels belong to the third order and are revered as commanders of other angels. They are mentors and heralds of the Lord’s will among people; through them God sends His Revelations to the righteous.

The Archangel Gabriel is usually called the second in the hierarchy after the Archangel Michael, the Archistrategos. Not all the Church Fathers agreed to recognize this particular place of Gabriel in the hierarchy. St. Andrew of Crete wrote that only a spirit who is constantly in the presence of God, closest to the throne of the Lord, could be awarded the right to carry the message about Christ’s upcoming birth. Thus, Gabriel should not be considered an archangel, but a seraph (the supreme angel). Saint Gregory the Great believed that just like Eve was tempted by the Prince of Darkness himself, only a seraph could have come to Mary who had a “flaming Seraphim’s love” for the Lord. However, the official church tradition calls Gabriel an Archangel and a “servant of miracles.” The archangel says the following in the text of the Gospel: “I am Gabriel, that stand in the presence of God” (Luke 1:19).

Most often, a mirror made of green jasper is depicted in the hands of the Archangel Gabriel as a sign of the messenger who “announces salvation of humankind” and a lantern with a burning candle. St. Dimitry of Rostov explains this attribute by the fact that the providence of God is hidden and only those are granted the ability to comprehend it who “always look into the mirror of the word of God and their own conscience.”

Although all heavenly forces are disembodied by nature, they appear to people in the form that is accessible and familiar to human perception. That is why, at the dawn of Christianity, when early Christians drew images on the walls of the catacombs, the Archangel Gabriel appeared as a beautiful man or a young boy without a halo and wings, dressed in a tunic and pallium (a band of lamb’s wool, a symbol of the archbishop’s power).

Later, a canon of depicting angels was formed: it prescribed to paint them with youthful faces, a halo, usually white wings, a tiara or a headband, symbolizing that the attention of the heavenly messengers was focused on the will of God. Sometimes the image was complemented by lavish robes.