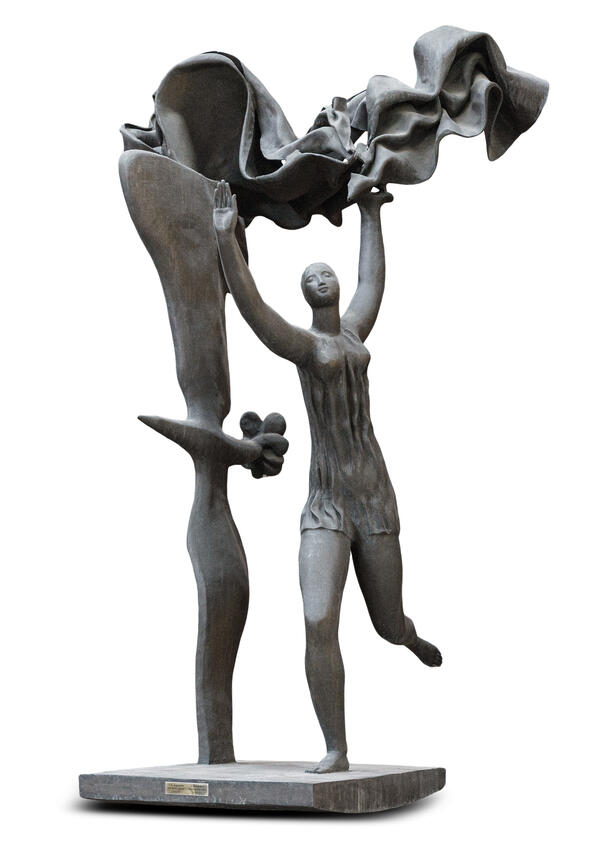

A sculpture from the museum collection depicts a character from the Book of Judith, included in the Old Testament. It tells the story of a righteous Jewish widow who saved her city, Bethulia, from the Assyrian invasion.

A large army of Assyrians, led by their commander Holofernes, invaded Judea and besieged the city of Bethulia. Judith, an honest and God-fearing young widow, lived there. The enemies cut off the residents’ access to the water supply, leaving them to die.

Judith dressed in beautiful clothes and went into the enemy camp together with her loyal maid. She gained the trust of the enemy general Holofernes. One night, as he lay in a drunken stupor, she decapitated him and returned home. Left without their leader, the enemy army fled in terror. Judith went back to her life and remained unmarried for the rest of it.

Judith was honored and respected throughout her life. She lived to be 105, and after her death, all the people mourned for seven days.

The image of Judith has been interpreted by artists throughout the centuries, in various styles and media. Her story took place at various times and in various locations, and artists had a choice of how to portray her. Botticelli depicted her returning home, while Rubens and Caravaggio showed her decapitating the general. Giorgione portrayed her against a peaceful landscape with a hazy image of the city in the background.

This is not just a reflection of the biblical story, but also an appeal to eternal questions about life and death, good and evil.

The mahogany composition created by Alexander Burganov stands out for its unusual sculptural design and abstract female image.

In combination with the

material, the image takes on a mystical quality. It features her lush hair flowing

in the wind, her large dress puffs, and her breasts, together with a somewhat

schematic figure and a free interpretation of the body. All these elements

create not just a character from the Bible but an archetypal figure of a female

defender and warrior. She is calm and still, nonchalantly holding on to the

head of Holofernes. This image is not about a fierce physical struggle, war, or

battle, but rather about the universal truth that good will always triumph over

evil through the power of love. This idea places this work not only in the

context of the Bible but also in the realm of eternal philosophical questions

that have preoccupied mankind since the beginning of time.