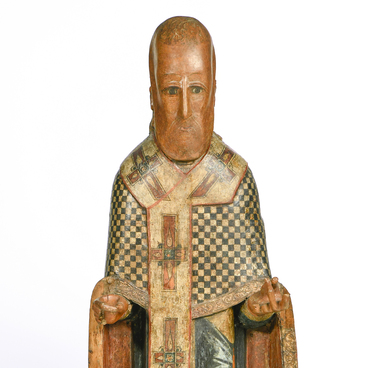

The wooden statue from the Museum of the History of Orthodoxy in Siberia depicts St. John the Evangelist — one of the 12 apostles. This statue was part of a multi-figure composition which featured the scene of Christ’s execution. The images of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist at the cross are “standing at the Crucifixion” in the Orthodox tradition.

The sculpture was made by an unknown artist in the 18th century. St. John is depicted as a young man — he has no beard, and his long wavy hair reaches the shoulders. His right hand is pressed to his cheek; his left arm is bent at waist level. According to the artist’s idea, his face looks sad, he is down in the mouth, and his eyes are thoughtful and mournful.

The sculptor meticulously rendered St. John’s garment: the apostle wears a long green chiton with a light twisted belt, a red cloak with a clasp in the form of a flower. Beneath the hem of the chiton we can see the apostle’s bare feet.

Wooden sculptures became popular in Siberian temples at the end of the 17th century. The Holy Synod attempted to ban religious statues, but northern craftsmen continued making them. The first sculptures were not elaborate: the sculptors roughly sketched faces, hair, and clothes, but did not carve any details. By the 18th century, sculptures had become increasingly refined and realistic. Since then, masters have tried to make facial features more naturalistic, they applied proportion, added fine details, and decorated them with carvings.

The main material for Siberian church statues was pine. This material was resistant to moisture and vermin, did not crack with time, and was easy to work with. Small elements like crowns of thorns or crosses, and sometimes faces and hands were carved from softer sorts of woods such as linden or birch.

Masters never worked with raw material. Blanks were made in the summer to have time to dry in the sun. The core was often removed so that the finished piece would be less deformed. Sculptures were carved from a single piece of wood or glued together from separate parts. They were covered with pieces of special hemp or linen cloth called “pavoloka” so as not to use fasteners.

The sculpture was made by an unknown artist in the 18th century. St. John is depicted as a young man — he has no beard, and his long wavy hair reaches the shoulders. His right hand is pressed to his cheek; his left arm is bent at waist level. According to the artist’s idea, his face looks sad, he is down in the mouth, and his eyes are thoughtful and mournful.

The sculptor meticulously rendered St. John’s garment: the apostle wears a long green chiton with a light twisted belt, a red cloak with a clasp in the form of a flower. Beneath the hem of the chiton we can see the apostle’s bare feet.

Wooden sculptures became popular in Siberian temples at the end of the 17th century. The Holy Synod attempted to ban religious statues, but northern craftsmen continued making them. The first sculptures were not elaborate: the sculptors roughly sketched faces, hair, and clothes, but did not carve any details. By the 18th century, sculptures had become increasingly refined and realistic. Since then, masters have tried to make facial features more naturalistic, they applied proportion, added fine details, and decorated them with carvings.

The main material for Siberian church statues was pine. This material was resistant to moisture and vermin, did not crack with time, and was easy to work with. Small elements like crowns of thorns or crosses, and sometimes faces and hands were carved from softer sorts of woods such as linden or birch.

Masters never worked with raw material. Blanks were made in the summer to have time to dry in the sun. The core was often removed so that the finished piece would be less deformed. Sculptures were carved from a single piece of wood or glued together from separate parts. They were covered with pieces of special hemp or linen cloth called “pavoloka” so as not to use fasteners.