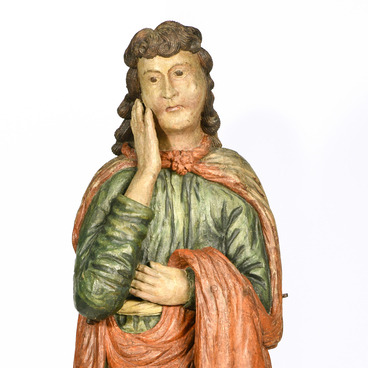

Christian artists often paint or sculpt the figures of people standing at the Cross who were witnesses to the crucifixion. The Mother of God and John the Apostle are featured in this way most often.

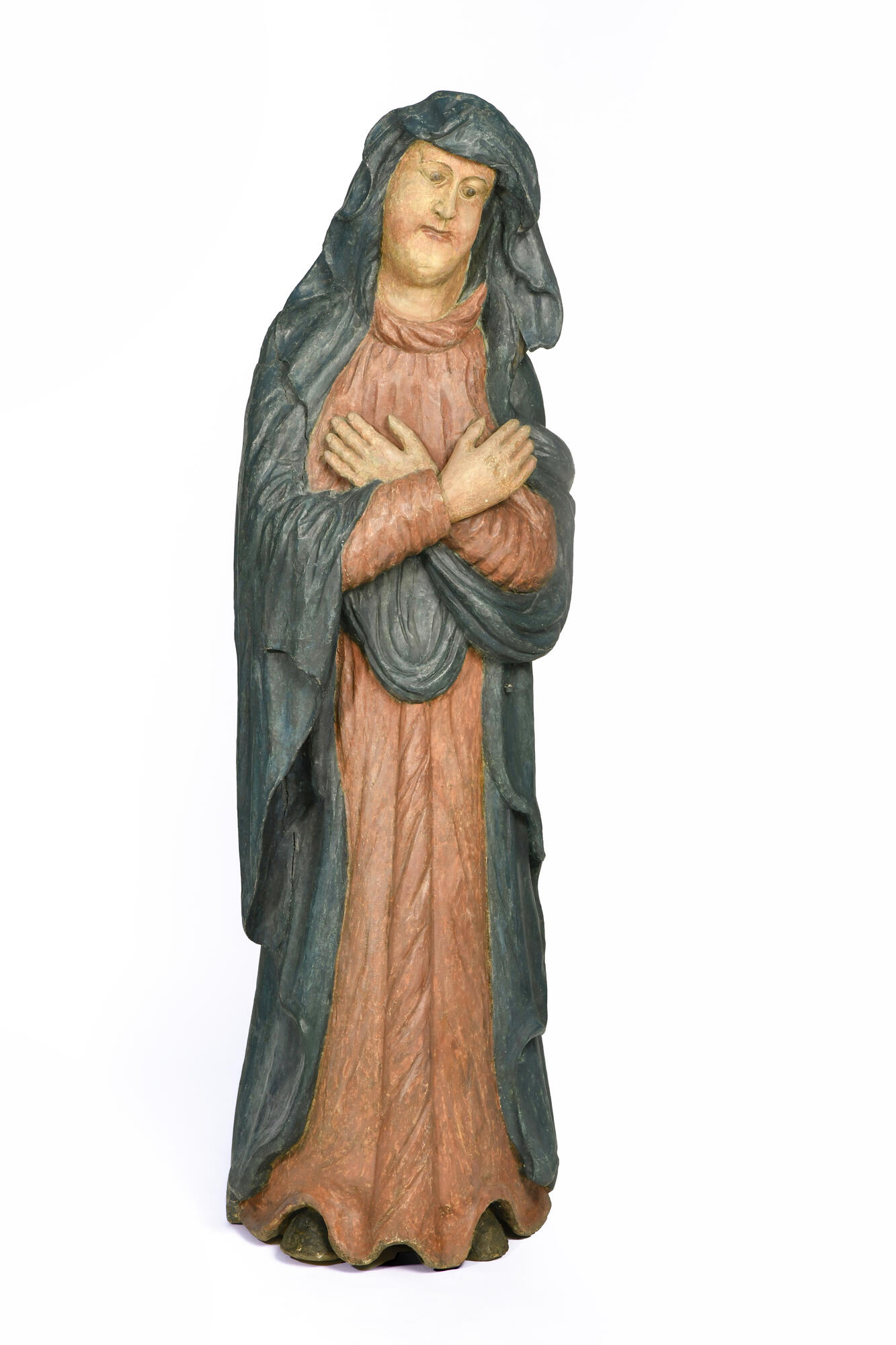

The carved wooden sculptures with the images of saints “standing at the Crucifixion” appeared in Russian Orthodox churches in the middle of the 17th century. The Bishop’s House collection contains a sculpture that was created later — an unknown master made it in the 19th century. He carved a full-size figure of the Virgin, with her arms crossed and her head slightly tilted to one side. The Mother of God wears a long red chiton and a dark blue veil — a maphorion. It fits tightly round the top of the head and entirely covers the hair. The Virgin looks down in grief. Her facial features and hands are quite large. Such images were common in the Siberian Orthodox art, and they differ greatly from the traditional iconography, where faces have fine Byzantine features.

The Russian Orthodox Church disapproved of wooden church figures for a long time. Many Patriarchs believed that religious sculpture was borrowed from “pagans” and “Catholics”, so it was close to ancient idols and Catholic statues, and therefore alien to Russian culture. In 1722, the Holy Synod issued a decree prohibiting the sculptural images of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints to be used in church services. More than a century later, in 1832, Emperor Nicholas I tightened the requirements: only painted icons were allowed.

However, in Northern governorates, artisans continued carving wooden sculptures. They were kept secret, hidden at home or in hidden rooms in churches.

Most often, the sculptures of the New Testament characters were carved from pine: this type of wood was durable and easy to work with. Small parts were made of softwood such as linden or birch. The wood was carefully dried and the core was usually removed since over time a sculpture that was hollow inside cracked less.

The sculpture’s protruding parts were always carved separately and then fastened with wooden pins and glue. The figure was polished, sometimes covered with canvas and primed, but more often, the wooden surface was painted. Subdued colors were selected to emphasize the relief more.

The carved wooden sculptures with the images of saints “standing at the Crucifixion” appeared in Russian Orthodox churches in the middle of the 17th century. The Bishop’s House collection contains a sculpture that was created later — an unknown master made it in the 19th century. He carved a full-size figure of the Virgin, with her arms crossed and her head slightly tilted to one side. The Mother of God wears a long red chiton and a dark blue veil — a maphorion. It fits tightly round the top of the head and entirely covers the hair. The Virgin looks down in grief. Her facial features and hands are quite large. Such images were common in the Siberian Orthodox art, and they differ greatly from the traditional iconography, where faces have fine Byzantine features.

The Russian Orthodox Church disapproved of wooden church figures for a long time. Many Patriarchs believed that religious sculpture was borrowed from “pagans” and “Catholics”, so it was close to ancient idols and Catholic statues, and therefore alien to Russian culture. In 1722, the Holy Synod issued a decree prohibiting the sculptural images of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints to be used in church services. More than a century later, in 1832, Emperor Nicholas I tightened the requirements: only painted icons were allowed.

However, in Northern governorates, artisans continued carving wooden sculptures. They were kept secret, hidden at home or in hidden rooms in churches.

Most often, the sculptures of the New Testament characters were carved from pine: this type of wood was durable and easy to work with. Small parts were made of softwood such as linden or birch. The wood was carefully dried and the core was usually removed since over time a sculpture that was hollow inside cracked less.

The sculpture’s protruding parts were always carved separately and then fastened with wooden pins and glue. The figure was polished, sometimes covered with canvas and primed, but more often, the wooden surface was painted. Subdued colors were selected to emphasize the relief more.