Over two centuries ago, a village called Srostki appeared near the Chuya Highway, in the foothills of the Altai Mountains, on the right bank of the Katun River. This is where two cousins, Ivan Popov and Vasily Shukshin, spent their childhood. Srostki was founded in the early 19th century by settlers from villages located on the Biya River — Bolshoy Ugrenevoy, Usyatsky, and Shubenka. However, most of the villagers descended from immigrants who came from Western Russia in the second half of the 19th century.

Vasily Shukshin wrote at the beginning of his memoirs “My Native Village”, “The village was founded in the 1860s, during the sad process of the migration from Central Russia to the free lands in Siberia. At first, there were several small villages, and over time, they fused together to form Srostki. As a result, there were several districts with their own customs and dialects within one village. There were five districts — the Baklan, Nizovka, Mordva, Dikari, and Golozhopka. The Baklan were the native Siberians, also known as the Chaldons. They were moody, well-built, and had prominent cheekbones. The men walked slowly with their hands in their pants pockets, with condescending or even contemptuous looks on their faces. They did not talk much except with their own people. They were hard-working and frugal people who counted every kopeck. They were all fishermen and hunters. Every one of them had a boat. They knew the Katun fifty miles upstream and downstream. They preferred to avoid fighting but were good at it…

The Nizovka people were a mixture of the Chaldons and the ‘Russians’. These were handsome men but rather belligerent, always at daggers’ points with the Chaldons.

The Mordva, Dikari, and Golozhopka were ‘tribes’ — the Popov, Bedarev, Degtyaryov, Dokuchayev, Brovkin, and Kolokolnikov families. These were large areas, full of noise and singing. The people spoke in their own dialects… These were grain growers, horsemen, and carpenters. If they had a feast, it was everything all at once — mayhem, knife fighting, and songs that made you cry every time. They were witty in both words and action… The men were not as big as in Baklan or Nizovka, but they were dexterous and tight-knit. If something was beyond one’s power, one would bring a horde. They loved their land, not many of them were hunters or fishers. They knew a lot about farming, about horses… They respected those who knew how to keep the house right. There were large families there, and everyone was related.”

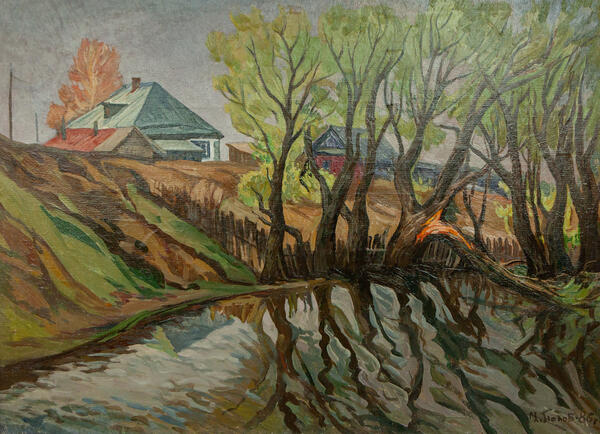

Shukshin’s words about his native village sound like a leitmotif for the painting by Ivan Popov, “Srostki. The 1930s”. The cousins had to grow up during this difficult period. It was also a time of political repression that fully affected the inhabitants of the village of Srostki and the close friends of Ivan and Vasily.

Shukshin’s words about his native village sound like a leitmotif for the painting by Ivan Popov, “Srostki. The 1930s”. The cousins had to grow up during this difficult period. It was also a time of political repression that fully affected the inhabitants of the village of Srostki and the close friends of Ivan and Vasily.

In his painting, Ivan Popov depicted the village in the 1930s. It is a winter landscape set against the background of Mount Biket, featuring wooden houses with snow-covered roofs, and haystacks in the yards. The image of the village of Srostki is a reflection of the childhood memories of Vanya and Vasya Popov. Both had to leave the village, missed it greatly, and felt the need to tell the world about this wonderful area and its people. Both chose their own path to do so through their art.

In fact, all the works by Ivan Popov and Vasily Shukshin reflected their native village of Srostki “which filled its children with energy and gave them wings.”