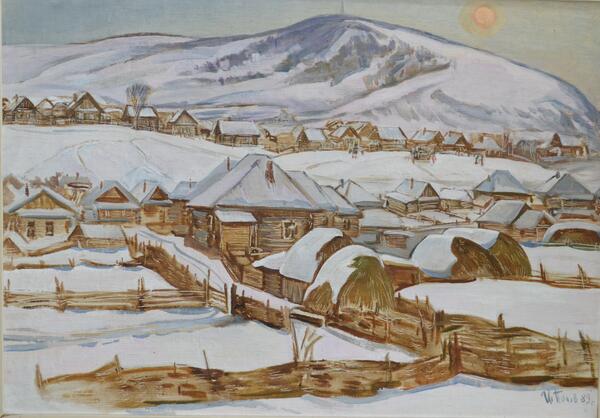

Ivan Petrovich Popov and Vasily Makarovich Shukshin left their native village of Srostki at an early age. Ivan Popov’s mother Stepanida Konstantinovna took him away when he was 13. Exhausted by all the hardship, she wanted to make life easier for herself and her son. Vasily Shukshin decided to leave and enroll in an automobile technical college when he was almost 17.

Later, Vasily Shukshin recalled, “I was coming on seventeen when, early one spring morning, I left home. I still wanted to take a run, brace my legs and slide along the smooth ice, clean and transparent as glass, instead of which I was having to strike out into the unknown vastness of grown-up life where I had neither kin nor acquaintance. I felt sad and rather frightened. My mother accompanied me out of the village, made the sign of the cross over me to keep me on my way, sat down on the ground and burst into tears. I understood her pain, and understood that she, too, was afraid, but evidently it is still greater suffering for mothers to see their children go hungry. My sister remained behind. She was still a child. And I was old enough to go. So I went.”

Back then, it seemed that Vasily Shukshin was leaving home to earn a living and to help his mother. Only time would show that he actually left home to find himself and his way in life, to become who he really was — a man of art. Later, after dropping out of the technical college in Biysk, he received a school certificate in his native Srostki, Vasily Shukshin would go far away, to Moscow, to enroll in the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). Every time, it was harder and harder for him to leave home. Much later, Vasily Shukshin reflected these overwhelming feelings in his films and writings.

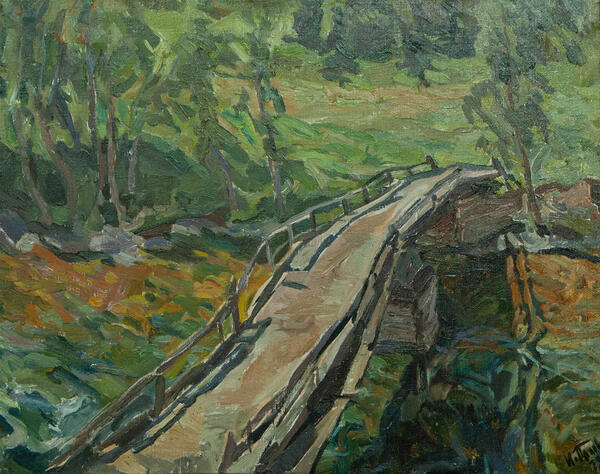

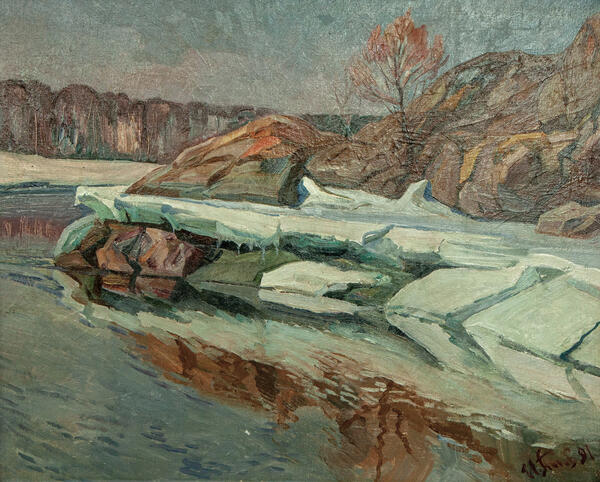

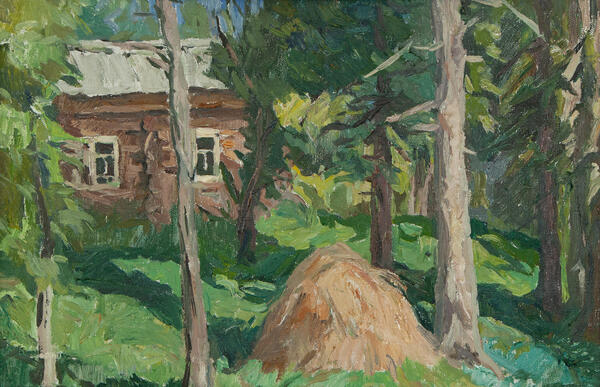

Ivan Popov understood his cousin’s feelings like no one else, as he felt the same. The painting “Farewell to the Katun” is a metaphor reflecting his thoughts about his native land and the sadness of leaving it. The cousins were fond of the Katun River because their childhood and many of its happy memories, such as fishing and visiting the islands, were associated with the river. “Farewell to the Katun” was also a farewell to their motherland, their beloved village of Srostki.

Vasily Shukshin wrote, “There is a river in the

Altai — the Katun. A river, white with anger, leaping over stones, hurling

itself at their cold breasts in high, furious waves, roaring — tearing its way

out of the mountains. Then all of a sudden, in the valley, it grows tame, and

all is silent, you can hear a duck dabbling on the other side of the islet. The

river is at rest. Clean, translucent, every pebble is visible on the bottom,

every grain of sand. One should try sitting on the beach at sunset… It is so

beautiful that it could not possibly be described in words.”