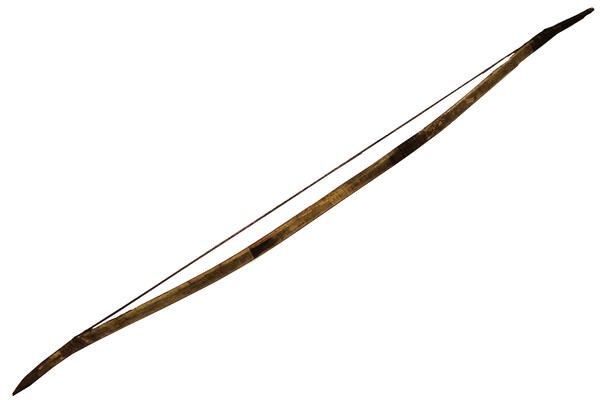

The people of the north had two types of bows — simple and complex. The simple one was a flexible, arched shaft that was cut from a piece of coniferous or deciduous wood. The ends of the shaft were tied together with a grass string. Complex bow consisted of several parts, and each of them had its own name: the middle of the shaft was called the handle, the ends were called fingers, the joints of the parts were knots, and the long elastic parts between the handle and the ends were called horns or shoulders. The simple bow was usually longer, but lighter than a complex one.

The showpiece presented at the museum refers to a simple type of bow. To make it from a chunk, the carved shaft was soaked in water and then shaped. A string made of strong grass was attached to the ends of the bow. The joints were fixed, and the bow was covered with thin strips of birch bark — to prevent it from moisture. Most often, sturgeon or pike glue was used for pasting.

Making a complex bow took a lot more time, resources and skill. The backrest was made of durable resinous coniferous wood. The blanks were dried for two or three days, cut with an ax, shaped into planks and bent on a wooden arch. To preserve their shape, they were soaked in cedar resin — heated over a fire and rubbed in the resin until it stopped being absorbed. Then the planks were cleaned of excess resin, tied with a cedar root (sargi) and glued.

The bound billets were dried for another day, after which fingers made from bird cherry bars were glued to them. The joints were firmly fastened with a solid coil of tendon threads. All the bows were tied with a sarga and dried, then scraped with a knife, pasted over with birch bark boiled in fish glue and dried again. The weapons were reinforced with bone and horn pads on the ends and on the handle. Sometimes the bow was ornamented with ownership marks.

Ket bows and arrows for hunting animals and birds were famous at North Yenisey and were the subject of exchange. For successful hunting, in addition to skill and an exceptional bow, according to beliefs, it was necessary to wear an amulet made of the skin of a piebald squirrel. In 1920, the bow as the main type of weapon was used only in a third of the Ket households. Modern methods of hunting had already supplanted in the 1930s.

The showpiece presented at the museum refers to a simple type of bow. To make it from a chunk, the carved shaft was soaked in water and then shaped. A string made of strong grass was attached to the ends of the bow. The joints were fixed, and the bow was covered with thin strips of birch bark — to prevent it from moisture. Most often, sturgeon or pike glue was used for pasting.

Making a complex bow took a lot more time, resources and skill. The backrest was made of durable resinous coniferous wood. The blanks were dried for two or three days, cut with an ax, shaped into planks and bent on a wooden arch. To preserve their shape, they were soaked in cedar resin — heated over a fire and rubbed in the resin until it stopped being absorbed. Then the planks were cleaned of excess resin, tied with a cedar root (sargi) and glued.

The bound billets were dried for another day, after which fingers made from bird cherry bars were glued to them. The joints were firmly fastened with a solid coil of tendon threads. All the bows were tied with a sarga and dried, then scraped with a knife, pasted over with birch bark boiled in fish glue and dried again. The weapons were reinforced with bone and horn pads on the ends and on the handle. Sometimes the bow was ornamented with ownership marks.

Ket bows and arrows for hunting animals and birds were famous at North Yenisey and were the subject of exchange. For successful hunting, in addition to skill and an exceptional bow, according to beliefs, it was necessary to wear an amulet made of the skin of a piebald squirrel. In 1920, the bow as the main type of weapon was used only in a third of the Ket households. Modern methods of hunting had already supplanted in the 1930s.