Millstones, or a handmill, are located in the ‘Russian Izba’ complex (‘izba’ is the name of a Russian wooden house similar to a log cabin). Presumably, the milestones were made in the 19th century.

Long before the museum was opened, a detachment of soldiers led by commander Alexander Prometny had found the millstones in the abandoned village of Pokrovka, in the Tomsk district. Before the handmill entered the museum collection, it was kept in the Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments.

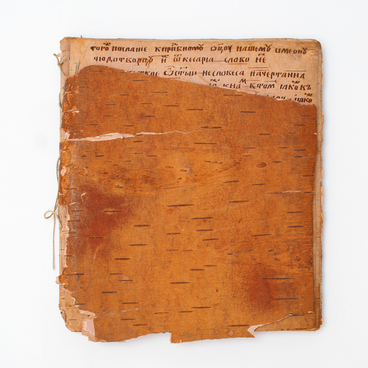

The millstones consist of two massive birch blocks, one above the other. They rest on four sturdy posts, which are cut into special grooves on the bottom and fixed with nails. The lower millstone is pulled together with a wooden hoop. There is a through-hole in the center of the upper one; grain was poured into it. A vertical handle, attached to the side, helped to rotate the millstone. The whole structure has darkened from time.

The woman put the grain into the hole of the upper millstone, rotated it, and soon received crushed grits, and with a longer rotation — flour. It was collected in a special tray, sifted through a sieve, the dough was made and bread was baked. The upper millstone was heavy, but children often helped grind the grain.

For better grinding of the grain, the surface between the millstones is covered with small metal plates; they are driven into the wood. Grinding was also improved by the birchwood itself, from which the handmill was made — it is considered one of the most durable materials.

Similar wooden mills were known throughout Siberia and in the Russian North, while in the southern provinces, stone devices were more often used.

More than a hundred years ago, millstones were in almost every house, including the villages of the Seversk closed administrative-territorial entity. With their help, the family could grind some flour or cereal. If more was required, the grain was usually transported for grinding to water mills, which were located in large villages.

The first millstones appeared several millennia ago; Vitruvius, a mechanic, and architect of Ancient Rome, described them in detail in his writings. Some researchers believe that the millstones became the ancient prototype of the wheel.

Long before the museum was opened, a detachment of soldiers led by commander Alexander Prometny had found the millstones in the abandoned village of Pokrovka, in the Tomsk district. Before the handmill entered the museum collection, it was kept in the Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments.

The millstones consist of two massive birch blocks, one above the other. They rest on four sturdy posts, which are cut into special grooves on the bottom and fixed with nails. The lower millstone is pulled together with a wooden hoop. There is a through-hole in the center of the upper one; grain was poured into it. A vertical handle, attached to the side, helped to rotate the millstone. The whole structure has darkened from time.

The woman put the grain into the hole of the upper millstone, rotated it, and soon received crushed grits, and with a longer rotation — flour. It was collected in a special tray, sifted through a sieve, the dough was made and bread was baked. The upper millstone was heavy, but children often helped grind the grain.

For better grinding of the grain, the surface between the millstones is covered with small metal plates; they are driven into the wood. Grinding was also improved by the birchwood itself, from which the handmill was made — it is considered one of the most durable materials.

Similar wooden mills were known throughout Siberia and in the Russian North, while in the southern provinces, stone devices were more often used.

More than a hundred years ago, millstones were in almost every house, including the villages of the Seversk closed administrative-territorial entity. With their help, the family could grind some flour or cereal. If more was required, the grain was usually transported for grinding to water mills, which were located in large villages.

The first millstones appeared several millennia ago; Vitruvius, a mechanic, and architect of Ancient Rome, described them in detail in his writings. Some researchers believe that the millstones became the ancient prototype of the wheel.