Lyudmila Ulamovna Passar was both an artist and a teacher: first, she studied in Nikolayevsk-on-Amur, then at the Herzen Institute in Leningrad.

In 1975, she was assigned to the Nanai village of Nizhniye Khalby, where she taught drawing and painting and headed art clubs. Despite her place of work being great (the Nizhniye Khalby school was located in a stone two-story building and had a separate dwelling just for teachers), Lyudmila Passar transferred to a modest-looking middle school in the village of Naikhin near her hometown. There, the young teacher began giving housekeeping lessons to girls and also taught an elective course in arts and crafts, all the while continuing her own creative work. Later, she got married and had children.

Soon, the Komsomolsk-on-Amur branch of the Artists’ Union noticed Passar’s unique skills and invited her to work in the artistic and industrial studios. The artist agreed, and in 1979, her works participated in a regional exhibition in Chita, earning praise from both the judging panel and the viewers.

The subsequent years were filled with creative trips and exhibitions and brought her recognition from colleagues and art critics. In 1991, Lyudmila Passar became a member of the Artists’ Union.

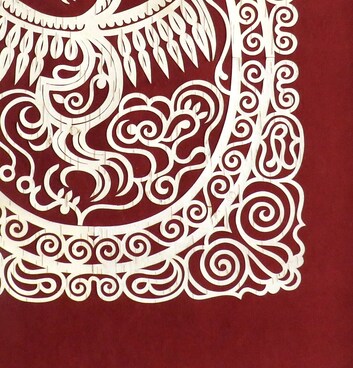

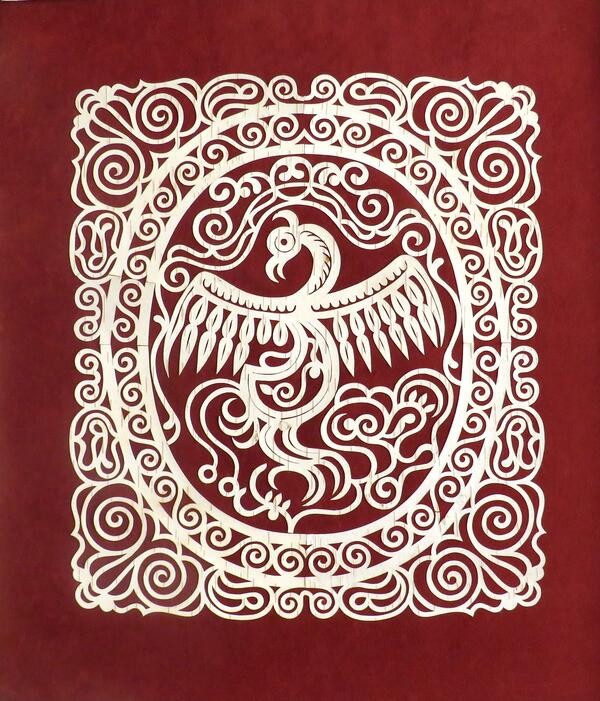

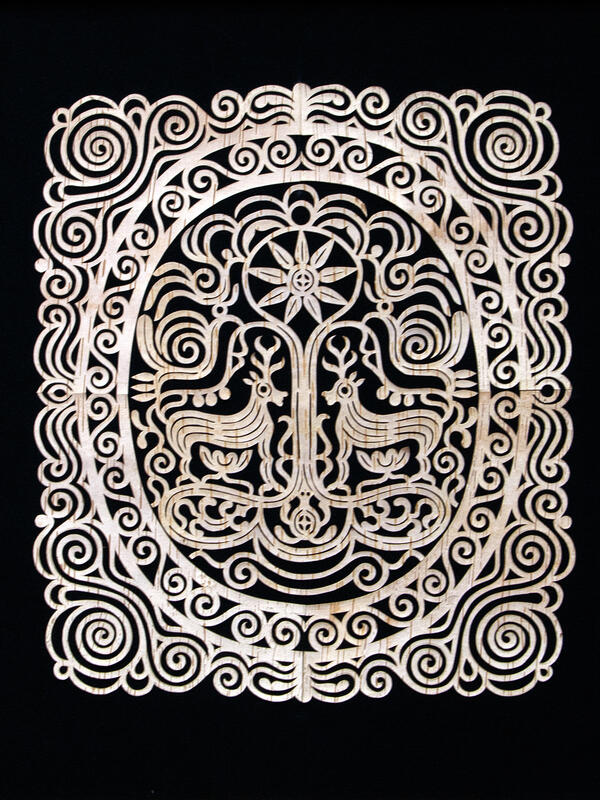

As a result of perfecting her signature style, studying the mythology and the ancient art of ornamentation, Lyudmila Passar created a series of heraldic panels, a number of illustrations with characters from the mythopoetic pantheon, and a huge birchbark triptych, dedicated to the legend of the Three Suns. Traditional ornaments in her works took on a heraldic meaning.

The folk art of the Nanai people is closely connected with mythology and nature worship. The majestic and severe Amur River with its serpentine curves and grayish-black waters has long been associated with a mighty dragon — both benevolent and cruel, demanding deference and tributes. According to Nina Ilyinichna Kaplan, a researcher of Far Eastern decorative art, it was the coils in the dragon’s appearance that formed the basis of a peculiar Amur ornament.

The dragon was believed to have three hypostases: the terrestrial dragon called Mudur, the heavenly one — Siymur and the water dragon — Puymur.

The displayed work of Lyudmila Passar also features dragons. The tiger, which several families considered their totem animal, was revered as the servant of the Mudur dragon, who passed on people’s requests to him.

Following the tradition of the Amur craftsmen, the artist depicted the tiger in the form of a mask, creating an allegorical image and showing strong veneration of the sacred animal. In the interweaving lines, one can distinguish a nose, a mouth slightly ajar, flattened ears, and four stripes on the body of the tiger that seems to be looking up at the Master Dragon.

In 1975, she was assigned to the Nanai village of Nizhniye Khalby, where she taught drawing and painting and headed art clubs. Despite her place of work being great (the Nizhniye Khalby school was located in a stone two-story building and had a separate dwelling just for teachers), Lyudmila Passar transferred to a modest-looking middle school in the village of Naikhin near her hometown. There, the young teacher began giving housekeeping lessons to girls and also taught an elective course in arts and crafts, all the while continuing her own creative work. Later, she got married and had children.

Soon, the Komsomolsk-on-Amur branch of the Artists’ Union noticed Passar’s unique skills and invited her to work in the artistic and industrial studios. The artist agreed, and in 1979, her works participated in a regional exhibition in Chita, earning praise from both the judging panel and the viewers.

The subsequent years were filled with creative trips and exhibitions and brought her recognition from colleagues and art critics. In 1991, Lyudmila Passar became a member of the Artists’ Union.

As a result of perfecting her signature style, studying the mythology and the ancient art of ornamentation, Lyudmila Passar created a series of heraldic panels, a number of illustrations with characters from the mythopoetic pantheon, and a huge birchbark triptych, dedicated to the legend of the Three Suns. Traditional ornaments in her works took on a heraldic meaning.

The folk art of the Nanai people is closely connected with mythology and nature worship. The majestic and severe Amur River with its serpentine curves and grayish-black waters has long been associated with a mighty dragon — both benevolent and cruel, demanding deference and tributes. According to Nina Ilyinichna Kaplan, a researcher of Far Eastern decorative art, it was the coils in the dragon’s appearance that formed the basis of a peculiar Amur ornament.

The dragon was believed to have three hypostases: the terrestrial dragon called Mudur, the heavenly one — Siymur and the water dragon — Puymur.

The displayed work of Lyudmila Passar also features dragons. The tiger, which several families considered their totem animal, was revered as the servant of the Mudur dragon, who passed on people’s requests to him.

Following the tradition of the Amur craftsmen, the artist depicted the tiger in the form of a mask, creating an allegorical image and showing strong veneration of the sacred animal. In the interweaving lines, one can distinguish a nose, a mouth slightly ajar, flattened ears, and four stripes on the body of the tiger that seems to be looking up at the Master Dragon.