Sewing and needlework were one of the basic components of women’s education in the Russian Empire. These skills enabled poor urban women to earn a living and to contribute to the family budget; they could work at home without violating traditional family rules.

By the 1870s sewing had become a compulsory subject for all female pupils in primary and secondary schools. Between 1860 and 1914, hundreds of sewing workshops and schools were established where girls and women were taught the crafts of sewing, knitting, embroidery, and making hats and artificial flowers.

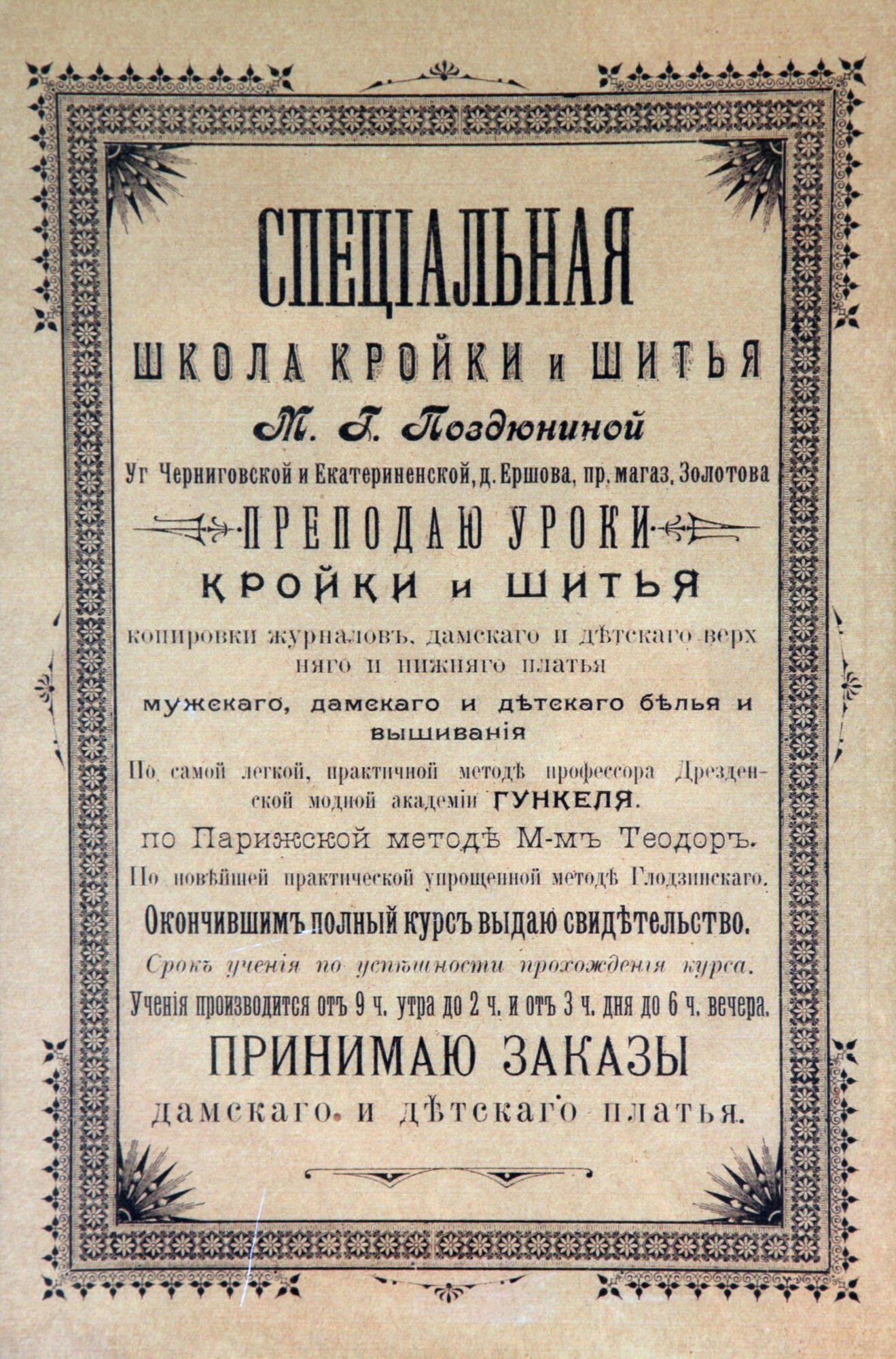

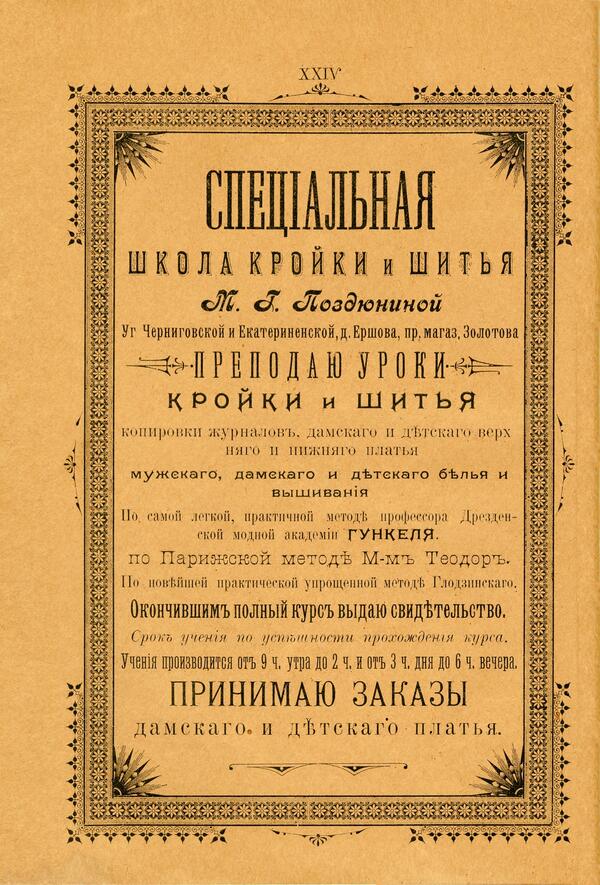

Women’s vocational schools trained between 20 and 50 students each. On average, a sewing course, depending on the establishment, intensity and duration, cost about 40 rubles a year. One such school in Tsaritsyn was run by M. G. Pozdyunina.

She claimed in her advertisement that she taught using the methods of Professor Gunkel from the Dresden Fashion Academy — there really was one at the time, although it is unlikely that ordinary people were aware of this professor.

The advertisement also mentioned Madame Theodore, the founder of the Parisian sewing courses. It also stated that the training was based on a manual by Xaverius Glodzinski. The book was published in 1893 in Warsaw by the author himself. At the school students could learn how to cut and sew men’s, women’s and children’s clothes. After successfully completing the course a certificate was issued.

Usually, if parents were able to find their child an apprenticeship in a dressmaker’s shop, a contract was signed with the master, stipulating the period of the apprenticeship. It could last from two to six years, with an average of four years.

The master provided the apprentice with accommodation and food, but it was not uncommon that the parents had to pay for their child’s clothing. After the contract was signed, parents would leave their offspring at the workshop and would not normally see them again until the apprenticeship was completed.

The First World War changed the situation in sewing dramatically: henceforth the vast majority of sewing establishments worked for the state. They made clothes for the soldiers at the front. The revolution of 1917 hit the sewing industry even harder.

By the 1870s sewing had become a compulsory subject for all female pupils in primary and secondary schools. Between 1860 and 1914, hundreds of sewing workshops and schools were established where girls and women were taught the crafts of sewing, knitting, embroidery, and making hats and artificial flowers.

Women’s vocational schools trained between 20 and 50 students each. On average, a sewing course, depending on the establishment, intensity and duration, cost about 40 rubles a year. One such school in Tsaritsyn was run by M. G. Pozdyunina.

She claimed in her advertisement that she taught using the methods of Professor Gunkel from the Dresden Fashion Academy — there really was one at the time, although it is unlikely that ordinary people were aware of this professor.

The advertisement also mentioned Madame Theodore, the founder of the Parisian sewing courses. It also stated that the training was based on a manual by Xaverius Glodzinski. The book was published in 1893 in Warsaw by the author himself. At the school students could learn how to cut and sew men’s, women’s and children’s clothes. After successfully completing the course a certificate was issued.

Usually, if parents were able to find their child an apprenticeship in a dressmaker’s shop, a contract was signed with the master, stipulating the period of the apprenticeship. It could last from two to six years, with an average of four years.

The master provided the apprentice with accommodation and food, but it was not uncommon that the parents had to pay for their child’s clothing. After the contract was signed, parents would leave their offspring at the workshop and would not normally see them again until the apprenticeship was completed.

The First World War changed the situation in sewing dramatically: henceforth the vast majority of sewing establishments worked for the state. They made clothes for the soldiers at the front. The revolution of 1917 hit the sewing industry even harder.