The carved wooden sculpture “Crucifixion” was made by an unknown master in the late 18th or early 19th century. The front side of the composition is three-dimensional, the reverse is flat: probably, the sculpture was placed close to the wall or it was suspended. The base is in the form of a low rocky hill and it symbolizes Calvary — the mountain on which, according to Holy Scripture, Jesus Christ was crucified.

The cross is eight-pointed — this is the most frequent variant of a cross in the Orthodox tradition. It is believed that besides the two main crossbeams, the instrument of execution of Christ had two shorter, additional ones: the slanting one was at the bottom, under the feet of the Savior, and the straight one was nailed above his head. There was a plaque on it with an inscription in three languages: “Jesus the Nazarene, the King of the Jews The sculptor placed the scroll with the first letters of this phrase above Christ’s head.

The image of Jesus is made in the technique typical of small sculpture. Unlike most church statues of the 18th century, where details were outlined only roughly, the creator of this work tried to convey the anatomy of the human body as accurately as possible. His Christ has thin arms, a sunken abdomen and ribs showing through the skin. His head is bowed down and his eyes are closed. His thighs are covered by a broad strip of white cloth. The artist made some folds with a thin chisel. Drops of blood are painted scarlet, they drip from the wounds on his hands, feet, head and under his ribs.

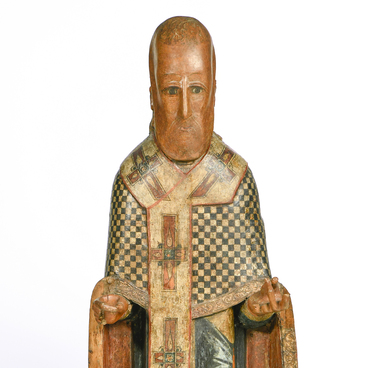

Wooden Orthodox sculpture was especially popular in the northern territories of Russia. In contrast to icon painting, there were far fewer characters: most often artists depicted Jesus in prison or on the cross, the Mother of God, St. John the Evangelist and Nicholas the Wonderworker. There were also statues of local Siberian saints: Metropolitan Philaret, St John, St Innocent, St Philotheus and others.

In some provinces, it was customary that the statues did not have traditional Byzantine features, but looked like those indigenous peoples who lived there. The figures of Christ with noticeable Bashkir or Komi-Permyak features have survived to this day.

The vestments of the sculptures were most often carved from a single piece of wood. But sometimes parishioners decorated them — they sewed clothes and shoes for the statues and donated precious crowns to the church.

The cross is eight-pointed — this is the most frequent variant of a cross in the Orthodox tradition. It is believed that besides the two main crossbeams, the instrument of execution of Christ had two shorter, additional ones: the slanting one was at the bottom, under the feet of the Savior, and the straight one was nailed above his head. There was a plaque on it with an inscription in three languages: “Jesus the Nazarene, the King of the Jews The sculptor placed the scroll with the first letters of this phrase above Christ’s head.

The image of Jesus is made in the technique typical of small sculpture. Unlike most church statues of the 18th century, where details were outlined only roughly, the creator of this work tried to convey the anatomy of the human body as accurately as possible. His Christ has thin arms, a sunken abdomen and ribs showing through the skin. His head is bowed down and his eyes are closed. His thighs are covered by a broad strip of white cloth. The artist made some folds with a thin chisel. Drops of blood are painted scarlet, they drip from the wounds on his hands, feet, head and under his ribs.

Wooden Orthodox sculpture was especially popular in the northern territories of Russia. In contrast to icon painting, there were far fewer characters: most often artists depicted Jesus in prison or on the cross, the Mother of God, St. John the Evangelist and Nicholas the Wonderworker. There were also statues of local Siberian saints: Metropolitan Philaret, St John, St Innocent, St Philotheus and others.

In some provinces, it was customary that the statues did not have traditional Byzantine features, but looked like those indigenous peoples who lived there. The figures of Christ with noticeable Bashkir or Komi-Permyak features have survived to this day.

The vestments of the sculptures were most often carved from a single piece of wood. But sometimes parishioners decorated them — they sewed clothes and shoes for the statues and donated precious crowns to the church.