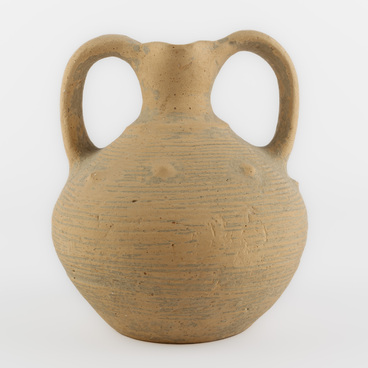

The museum displays a kumgan — a jug for water, used for washing the face and hands and for personal hygiene in accordance with the Islamic tradition. It is made of copper.

Copper dishes became common on the territory of Adygea at the turn of the 20th century, after the end of the Caucasian War. Traditionally, the Circassians used ceramics, but copper utensils proved much lighter, handier and more reliable at home and therefore soon became popular with the local people. Most copperware was made on the territory of modern Dagestan, where this craft was quite widespread. Copper products included weapon frames and various household utensils — cauldrons, dishes, basins, water vessels, pails, and mugs.

Copper tableware was in great demand, but the manufacturing process was quite expensive and laborious, so the abundance of such utensils in the house eventually became a sign of prosperity and wealth. To make dishes from copper, coppersmiths most often used the technique of stamping an item and its parts from a copper sheet, while cast dishes were rare. Initially, the elements (handles, lids) were attached to the main product with rivets. Later, the artisans used the techniques of soldering copper with brass, silver, and tin. To avoid the harmful effects of copper and to ensure a more hygienic use of water containers, artisans applied a wax-based mastic to the inner surface of the vessel. Later, they started using a tinning technique: from the inside, the surface of the dishes was covered with a thin layer of tin. Tinning protected the metal from external influences and adverse processes, in particular from corrosion. Often, the outer surface of the vessels was also tinned, and a pattern was engraved or chased.

With the increasing popularity of copper utensils, the services of itinerant coppersmiths were in great demand. The artisans traveled along the roads of the North and South Caucasus with all the necessary equipment: a hammer, a small anvil, tools for chasing, engraving, and repairing dishes.

This copper kumgan has a narrow neck and a soldered spout, a handle and a hinged lid attached to the vessel with copper rivets. It entered the museum’s collection in May 1949. The capacity of this jug is about two liters.

Copper dishes became common on the territory of Adygea at the turn of the 20th century, after the end of the Caucasian War. Traditionally, the Circassians used ceramics, but copper utensils proved much lighter, handier and more reliable at home and therefore soon became popular with the local people. Most copperware was made on the territory of modern Dagestan, where this craft was quite widespread. Copper products included weapon frames and various household utensils — cauldrons, dishes, basins, water vessels, pails, and mugs.

Copper tableware was in great demand, but the manufacturing process was quite expensive and laborious, so the abundance of such utensils in the house eventually became a sign of prosperity and wealth. To make dishes from copper, coppersmiths most often used the technique of stamping an item and its parts from a copper sheet, while cast dishes were rare. Initially, the elements (handles, lids) were attached to the main product with rivets. Later, the artisans used the techniques of soldering copper with brass, silver, and tin. To avoid the harmful effects of copper and to ensure a more hygienic use of water containers, artisans applied a wax-based mastic to the inner surface of the vessel. Later, they started using a tinning technique: from the inside, the surface of the dishes was covered with a thin layer of tin. Tinning protected the metal from external influences and adverse processes, in particular from corrosion. Often, the outer surface of the vessels was also tinned, and a pattern was engraved or chased.

With the increasing popularity of copper utensils, the services of itinerant coppersmiths were in great demand. The artisans traveled along the roads of the North and South Caucasus with all the necessary equipment: a hammer, a small anvil, tools for chasing, engraving, and repairing dishes.

This copper kumgan has a narrow neck and a soldered spout, a handle and a hinged lid attached to the vessel with copper rivets. It entered the museum’s collection in May 1949. The capacity of this jug is about two liters.